Arts and equalities journalist Paul F Cockburn asks how the consideration of accessibility has influenced the aesthetics of disability theatre and performance.

Necessity, according to the old proverb, is the mother of invention—and performance is no exception. Soon after Jenny Sealey MBE became Artistic Director of Graeae Theatre Company in 1997, she faced a significant problem—the company had a commitment to the Arts Council to do another show, but hardly any money. Certainly, there wasn’t anything to pay for the BSL interpreters and audio describers that were, by then, an intrinsic part of any Graeae production.

“I realised that everything had to be embedded in the text,” Jenny says now. “So I chose Steven Berkoff’s adaptation of The Fall of the House of Usher because he had written more stage directions than actual text. Beautiful stage directions; some of them about what was happening physically, some about what the light was like. I thought… why don’t the actors take on and embody those stage directions? Then we pre-recorded all the BSL signing, projecting the signer so he was like this sort of maverick character in the mirror above the bed, looking down. It was hell on earth trying to do it, but it all made sense, and I realised that everything is in the script about what the accessibility can be.”

In the decades since then, Jenny and Graeae have developed what has been called the “aesthetics of access”; essentially, the ways in which accessibility concerns are not simply last-minute add-ons but actually influence and shape the work in wonderful, unexpected ways. “If you start with that idea that you want to make your theatre accessible, look at the text,” Jenny insists. “As you start to unpack the text, that’s how you understand what the aesthetics are.”

The results are often unexpected. The cast of Graeae’s production of Sarah Kane’s Blasted spoke every single word she wrote, including stage directions, creating a real sense of claustrophobia. This year’s production of The House of Bernarda Alba incorporated elements of audio description into the script while including signing on stage—Jenny’s cast included three deaf actors and an actor-signer. “Finding the family relationship of the sisters—some who sign, some who use voice, some who are deaf and use voice, and some who don’t—allowed us to explore the authenticity of that family and their relationships, and the show suddenly just went where it had to.”

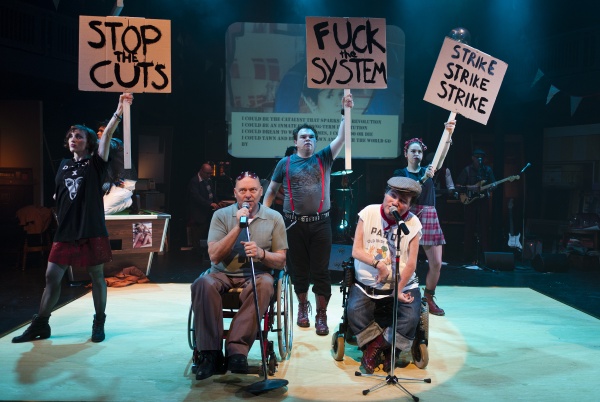

Garry Robson is an acclaimed actor, director and co-artistic director of Glasgow-based Birds of Paradise Theatre Company; for him it’s all about using access to add something to a performance. “The first time I saw accessibility writ large was in Graeae’s Ian Dury musical, Reasons To Be Cheerful, which I was with for several years,” he explains. “The lyrics were captioned in a really exciting way, using a lot of visuals, and all the punters loved it because it was like having a song sheet—they could join in! Also, the audio description was by a character called ‘Pickles’; a bit of a wheeler-dealer, a very Dury-esque character, who was completely visible on stage. Visually-impaired audience members had him in their ear, but it was all done in character. It got to the stage where people were asking for the audio description headsets because they were enjoying Pickles’ commentary!”

However, Garry accepts that including access for the sake of it doesn’t always work. “You can clutter a show, you can make it collapse under its own weight by trying to throw too much at it,” he says. “But the one thing we have discovered (at Birds of Paradise) is that if you’re serious about access, you have to embed it from the start of the creative process. It has to be budgeted for, for example; it’s not cheap to do. But once it’s in there at the beginning—I don’t mean at the start of rehearsals, but from when you’re thinking of putting on the show in the first place—then it makes you think again about everything you’re doing which, as an artist, is always exciting. No one is going to mark you down if you decide you don’t want to go ahead with it, but at least consider it.”

In recent years, “mainstream” theatres have begun to introduce specific, audio-described, BSL-interpreted and autism-friendly “relaxed” performances, but the general approach is not without problems. “I think you often find that things like captioning and interpreting are seen as the realm of Front of House rather than the artistic team,” says Garry. “That seems crazy to me: if you’re going to have captioning, you need to work with the lights; and not involving the interpreter in rehearsals is just shocking oversight, really.”

Yet there are signs that at least some non-disabled companies are beginning to “get” the aesthetics of access. “I was watching the new Complicite show, Beware of Pity,” says Garry. “A wonderful piece, I thought, but it was kind of almost audio described. Whether that’s just because Simon McBurney is open to working with deaf and disabled companies and performers, or it’s spreading into the mainstream, who knows?”

While Jenny accepts that there are now aspects of Graeae’s work that can be thought of as “a Jenny Sealey style of doing things”, she’s the first to underline how she’s always learning. “Every single play offers a different challenge; a new journey, a new exploration,” she insists. “I haven’t got a template. I think the day we have a template is the day I leave Graeae because Art cannot have a template. It makes it boring.”

“I have the play, I cast the best people for the job,” she says. “I’m really lucky to work with the teams of people I do, because although Graeae calls it an aesthetic, every single team we work with continues to unpack, excavate, renew, and are an inspiration of that aesthetic.”

Watch this British Council-commissioned film about the creative uses of sign language and audio description in theatre: